The European defense industry is struggling to cope with global competitive pressure

Mario Draghi, the former Italian Prime Minister and President of the European Central Bank, called for a radical policy change in his recently published report on EU competitiveness. In the event of inaction, Europeans risk deepening their dependence on other geopolitical powers, such as the US, for defense technology. Brussels lacks central management of the defense industry to define strategic objectives and promote the Europeanisation of supply chains.

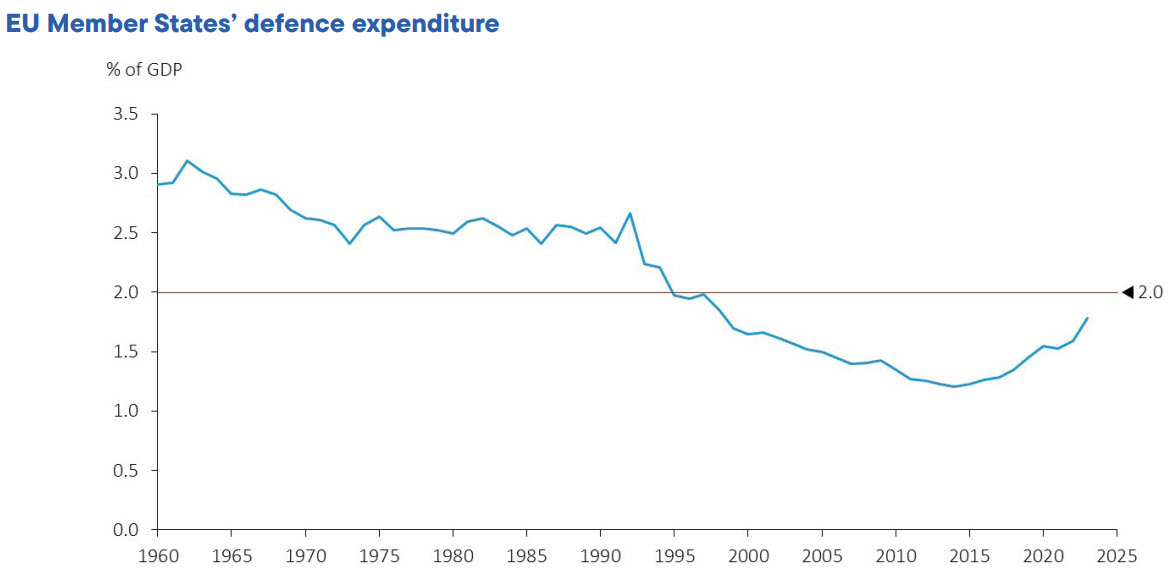

EU countries' defense spending is insufficient in the current geopolitical environment, according to the recently published Draghi report. Due to the long period of peace in most of Europe and the US security umbrella, military spending in the EU has been declining for fifty years. The absence of demand and long-term procurement planning has deprived the European defense industry of the ability to forecast future needs, which has subsequently resulted in a decline in industrial capacity. The trend of declining defense spending was partially reversed from 2014 onwards, with a significant increase in defense budgets following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

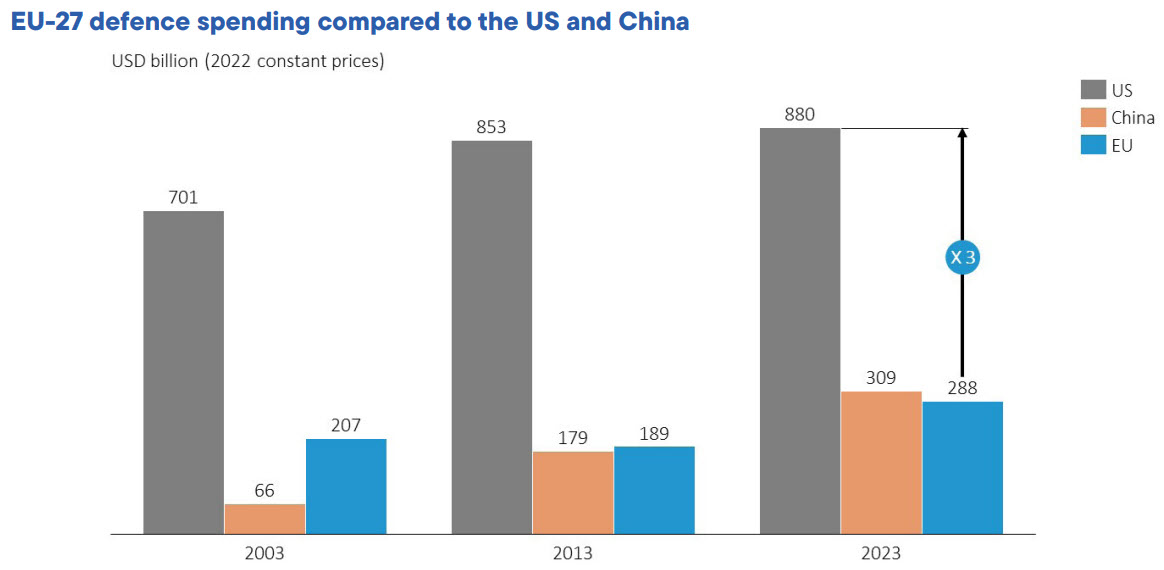

At present, however, European spending remains about one-third that of the US, while China is spending more and more on defense. According to the Swedish think tank SIPRI, the US allocated $916 billion to the defense department last year, while the cumulative spending of EU member states is estimated at $313 billion. China's defense budget appears to have reached $296 billion, but given the lack of official figures, it may be considerably higher. The US and China accounted for almost half of all global defense spending in 2023, with the US defense budget accounting for a 37% share (three times the Chinese share).

Only ten NATO member states spend more than 2% of their GDP on defense, in line with their commitments to the organization. If all EU and NATO member states below the 2% threshold were to meet the alliance's target, defense spending would increase by an additional €60 billion. Europe, due to underfunding, lacks the means to secure its strategic autonomy and keep pace with global competitors. However, new defense technologies require massive investment in the industry, which demands rapid political decisions at the pan-European level.

Moreover, EU investment in defense research and innovation is much lower than that of its industrial competitors, particularly the US. In 2022, Member States invested a total of €10.7 billion in defense R&D, nowhere near the US budget. The latter allocated $140 billion for research, development, and testing in 2023.

Despite several initiatives, European countries have so far been unable or unwilling to carry out a comprehensive consolidation and integration of the EU defense industrial base. Concerns related to national sovereignty and autonomy, as well as the reluctance of Member States to give up some industrial capabilities in favor of cross-border solutions, have hindered progress. In contrast, the US has pursued its defense industrial consolidation strategy very consistently. Since the end of the Cold War, it has reduced the number of key arms companies from 11 to five major players, which have been very successful in the global market.

Overcoming the duplication of industrial capabilities by promoting international intra-EU cooperation will, according to Draghi's report, lead to economies of scale and create more competitive European defense corporations. Only sufficiently large companies can develop new technologies (particularly interoperable "systems of systems") whose availability can benefit all European national armed forces in the future. The lack of EU standardization was fully demonstrated in the Ukrainian-Russian war when European states supplied Kiev with ten different types of howitzers using 155mm ammunition.

Foreign suppliers are taking advantage of the lack of production capacity in the EU. In recent years, most of Europe's investment in defense solutions has gone to US manufacturers, with Israel and South Korea also benefiting. The decision to 'buy US' is rooted in the legacy of the Second World War and the Cold War, and some of the EU elite are comfortable continuing in this direction. Of the €75 billion spent by member states between June 2022 and June 2023, 78% of procurement spending was redirected to purchases from non-EU-based arms companies. Sixty-three percent of this came from US-based companies, which increased their sales to Europe by 89% between 2021 and 2022.

In some cases, the choice to buy from the US may be justified because the EU cannot produce some products. But in many cases, European equivalents exist or could be quickly provided by the EU defense industry. At the same time, some US defense products are not always suitable for European needs, and the divergence of expectations from weapons will become even more pronounced in the future. Indeed, the US is adapting its military capabilities to respond to new threats in the Pacific.

Yet many EU members prefer to buy defense equipment from the US. As mentioned in a recent EU Competitiveness Report, the US government first supports the sale of military equipment from an administrative point of view—after signing an intergovernmental agreement, it handles the conclusion and administration of the contract with the industrial supplier. Secondly, many European countries are poorly informed about the actual supply of the European defense industry—symptomatic of the lack of demand consolidation by the EU political leadership. The real or perceived faster availability, perceived quality, and price of US products also play a role. Finally, Europeans often have closer ties with US military leaders than with each other and prefer interoperability with the US because they cannot imagine any military intervention without American involvement.

For historical reasons, the management of defense industrial policy at the EU level suffers from fragmentation and weakness. EU members have not had the political will or an effective mechanism for pooling resources and jointly financing, acquiring, maintaining, and upgrading defense products or technologies. Similarly, they have been mostly unwilling to integrate their defense industrial capabilities to achieve efficiencies and economically attractive volumes. The Union lacks a centralized body with a team of experts to manage industrial defense and security initiatives, provide funding from Brussels, or offer a clear political mandate to act in this field.

On March 5, 2024, the European Commission presented the first European Defense Industrial Strategy (EDIS) and the related European Defense Industry Programme (EDIP), a regulation implementing the Strategy’s measures. Both documents aim to address many of the challenges described in this article. EDIS and EDIP propose a set of measures to "spend more, better, together, and in a European way" in the field of security and defense. The proposed EDIP Regulation has been forwarded to the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union for examination. A vote by the legislators is likely to take place during the current term of the European Parliament.

These initiatives will hopefully lead to the development of a medium-term EU defense industrial policy that will define EU defense strategic objectives, promote cross-border cooperation, and lead to the Europeanisation of supply chains. For example, Mario Draghi calls for armaments companies to receive funding for the maintenance of temporarily idle production capacity, privileged access to raw materials and energy, and measures to allow for rapid expansion of production in case of urgent need.

EU policy must also focus on managing the demand for defense products and standardizing the equipment purchased. Increasing joint defense spending and procurement will create favorable conditions for further consolidation of industrial capabilities. The importance of defense industrial policy must also be reflected in the EU’s institutional setup, particularly by strengthening the Commission's coordinating role and establishing a Commissioner for Defense Industry with an appropriate structure and funding. Their role will include defining and implementing an EU defense industrial policy relevant to current geopolitical realities.