Trump 2.0 as a positive shock for the European Union: Will a single European army emerge?

Donald Trump’s victory in the U.S. presidential election signals a shift in U.S. strategic focus from Europe to the Indo-Pacific. His critical stance on NATO also weakens the sense of security among its European members, particularly those on the alliance’s eastern flank. According to some European leaders, Europe must seize this challenge to develop an independent security and defense policy, potentially creating a unified EU military force that is fully integrated and interoperable with NATO. However, the North Atlantic Alliance, with the U.S. at its head, should remain a crucial pillar of European defense.

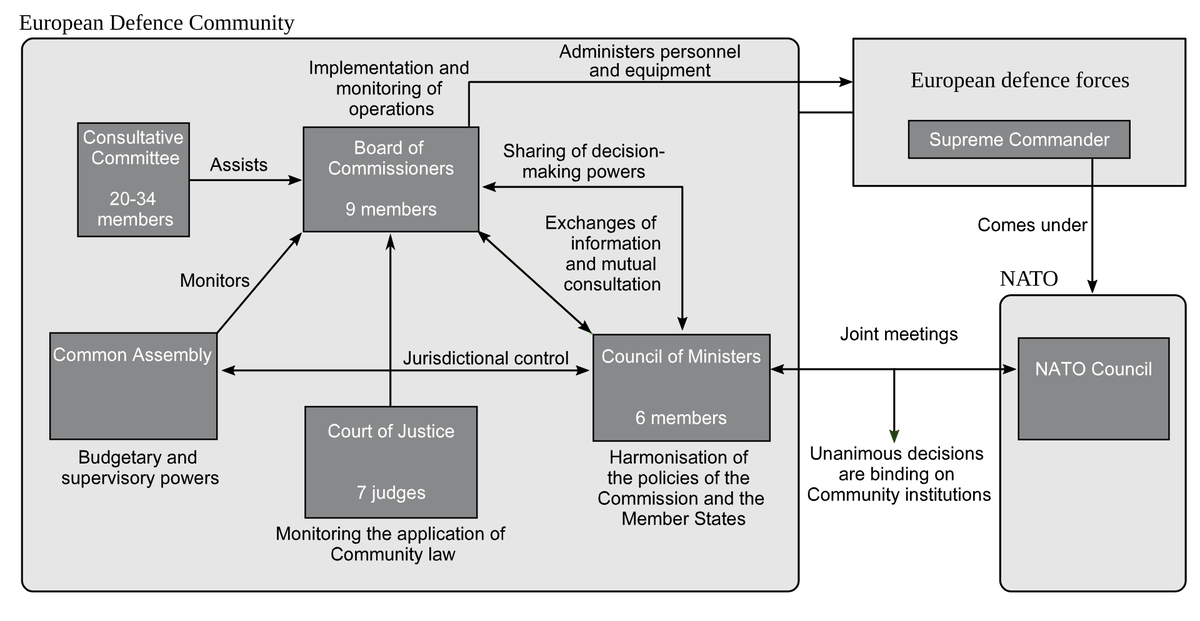

The concept of a European army has historical roots and nearly became reality shortly after World War II. At that time, plans envisioned a force of 43 divisions (14 French, 12 West German, 12 Italian, and 5 from the Benelux countries) under the political direction of a six-member council representing all participant nations. Yet, the plan for a European Defence Community, championed by French Prime Minister René Pleven, was ultimately rejected in Paris. In 1954, French parliamentarians declined to ratify the relevant international treaty, fearing excessive loss of national sovereignty.

Seventy years later, the EU faces mounting geopolitical challenges. These include the Russia-Ukraine war, evolving relationships with China and Russia, and instability in North Africa and the Middle East. While American and European perspectives on these issues often differ, the EU remains reliant on the United States and NATO’s leadership for security. Yet, President Trump questions American support for states that fail to meet their financial commitments to the alliance, even considering NATO itself "obsolete."

In recent years, Brussels has taken steps toward EU defense initiatives, particularly through funding programs that support military projects. Since 2017, PESCO (Permanent Structured Cooperation) has bolstered new weapons development, cyber security, and military training. Additionally, the European Defence Fund (EDF), with a planned budget of eight billion euros through 2027, backs projects to strengthen European strategic autonomy and foster industrial cooperation within the EU. The Strategic Compass, adopted in 2022, aims to enhance crisis management and establish an EU Rapid Deployment Capacity (EU RDC) of 5,000 troops by 2025.

Despite progress, significant challenges remain on the path to a European army. Funding is one of the largest obstacles, as many EU countries face constrained defense budgets. While Germany, France, and other member states have increased defense spending, these boosts often align with existing NATO commitments. A common defense policy also requires consensus, which remains challenging in a union of 27 nations with diverse security concerns. In Eastern Europe, countries like Poland and the Baltic states fear a European army could weaken ties to NATO, thereby diminishing deterrence credibility against Russia. NATO, with U.S. leadership, thus continues as the central pillar of European defense.

To tackle these challenges, some prominent European leaders see Trump’s re-election as an opportunity to pursue strategic autonomy. "We Europeans do not have to delegate our security to the Americans forever," French President Emmanuel Macron said, responding to Trump’s re-election. "This is a decisive historical moment for us Europeans. The question before us is: do we want to simply read history as others write it—wars by Vladimir Putin, American elections, Chinese decisions on technology or trade? Or do we want to write it ourselves? I believe we have the power to write it."

Luxembourg Prime Minister Luc Frieden supports Macron’s stance, associating the EU’s geopolitical sovereignty with the creation of a European army, permanent membership in the UN Security Council, the establishment of a multi-speed Europe, and the reform of Europol and Frontex. According to Frieden, Russia’s aggression in Ukraine highlights the urgency of these changes, and Trump’s election will drive the first political decisions.

"We need to discuss the need for a European army," Prime Minister Frieden asserted. He envisions not a replacement for "institutions that promote dialogue and democracy," but rather a force "capable of defending our values." Frieden sees this army as "fully integrated and interoperable with NATO."

To start, he proposes consolidating the armed forces of a coalition of countries willing to relinquish some sovereign rights to maximize defense efficacy. Politically, he advocates for major foreign policy decisions to be made by qualified majority rather than unanimity. "To realize Europe’s ambitions, we need to rethink our decision-making process... In politically sensitive areas, a superqualified majority could replace unanimity, preventing a single country from blocking decisions when there is broad consensus."

Frieden recognizes that enthusiasm for deeper defense integration varies across member states. He therefore proposes a multi-speed Europe, with different levels of integration. At the core, he envisions a group of highly integrated member states with quasi-federal elements, such as the euro, Schengen, a common foreign policy, and common defense. A second circle would consist of countries prioritizing economic cooperation and free trade. A third circle would offer candidate countries a concrete roadmap to EU membership. Finally, a fourth group would involve countries like Norway, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland, which wish to maintain some cooperation without joining the EU.

Frieden also sees Europol and Frontex reform as essential to updating EU migration policy and reinforcing external border control. He proposes transforming Frontex into a true European border guard with powers equivalent to national forces, supported by a unified return policy integrated into the EU’s visa and cooperation agreements with third countries. To strengthen the Schengen area, Frieden suggests enhancing police cooperation through a reformed Europol, "a European police agency with real executive powers in certain areas."

Many of Frieden and Macron’s proposals address core aspects of national sovereignty, which remain sacred for many politicians. Embracing these visions will require a shift in mentality, potentially driven by the existential threat facing the EU. With Trump’s victory, the U.S. commitment to NATO—the backbone of EU defense—may wane. Russia, meanwhile, watches for any signs of European weakness that could embolden it to threaten the Baltic states. Following Ukraine and the Baltics, Central and Eastern Europe could be next.

Beyond PESCO and the EDF, larger defense initiatives will likely emerge. In a multi-speed Europe, only defense companies from countries committed to deeper integration will likely gain access to these projects. Billions of euros are at stake, and as the EU seeks geopolitical autonomy, this figure is set to rise.