Russia boasts of hypersonic missiles. But it has few of them and systematically persecutes their developers and accuses them of treason

The Russians have already used dozens of Kinzhal hypersonic missiles in Ukraine and in at least one case Zirkon. Vladimir Putin himself likes to boast about this type of arsenal, although experts say Russia has only a limited number of these state-of-the-art missiles and their production is slow. Nevertheless, there has been a crackdown on the aggressor's side on those responsible for the operation of supersonic missile programmes - at least 12 physicists somehow linked to the development of these technologies have been arrested since 2015. All have been accused of treason by the Kremlin.

_10.jpg)

This seems like a story typical of Russia, especially in wartime, yet to outside observers it may seem illogical in its course. Vladimir Putin and his loyalists are systematically targeting some of the country's most valuable scientists and politically liquidating them in their twilight years. These are physicists in the field of advanced rocket and propulsion development, whose knowledge the Russians use to build and improve their hypersonic missiles. The Kremlin's authoritarian ruler often says that his country leads the world in this respect, yet he does not give much credit to those responsible for his proclaimed success.

According to the BBC's findings, there have been at least 12 arrests since 2015 of people either directly involved in these projects or working for institutions linked to them. Most are men of retirement age, three of whom are now deceased. One was abducted from his hospital bed by unknown perpetrators during the final stages of cancer and later died from complications. Among those arrested is a sixty-eight-year-old academic, Vladislav Galkin. Authorities raided his home in Tomsk, southern Russia, a year ago. Masked men detained Galkin at 4 a.m. and took a number of his scientific notes, according to relatives. He spent the first months of his imprisonment in solitary confinement, and his relatives are forbidden by the FSB secret service to talk about the case. All they know is that he has been charged with treason.

He was tried in the same court as his former colleague Valery Zvegintsev, with whom he had worked on several research projects. Both were named in an article in an Iranian scientific journal on air intake mechanisms for high-speed aircraft. The year before, the FSB had arrested two other colleagues of Zvegintsev from the same institute, the director and former head of the laboratory for work on high-speed aerodynamics. This led to the writing of an open letter by the staff of the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics. The demand for their dismissal on the basis of "excellent scientific results and loyalty to the interests of their country" was rejected and the notice posted on the Institute's website was deleted.

Treason can mean, among other things, the transfer of state secrets to foreign powers, which observers say is precisely the impression the Kremlin is trying to create; the attempt by foreign players to obtain prized military secrets. And since such trials are always held behind closed doors in Russia, the details of the charges can only be guessed at. But defense lawyers deny that they have divulged any information and that some of the charges are based on open and legal cooperation with foreign researchers.

"Hypersonics is a subject for which you are now obliged to put people in jail," Yevgeny Smirnov, a lawyer with First Division, a Russian human rights and legal protection organisation, told the BBC. He previously worked directly in Russia as a defence lawyer for scientists similarly accused of treason before moving to Prague after fearing for his life. "It's not about making rockets, it's about studying physical processes," Smirnov continued, adding that while these findings may be used later by weapons scientists, those arrested were purely studying scientific issues such as the deformation of metals at supersonic speeds or the effects of turbulence.

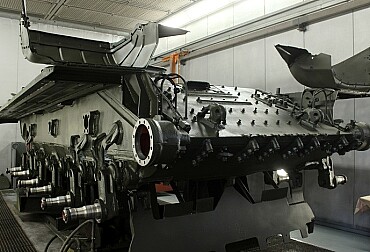

Russia currently uses two types of hypersonic missiles - the Ch-47M2 Kizhal and the 3M22 Zirkon. The former has been deployed more in Ukraine, yet on a limited scale. The Kizhal is fired by Russian fighters, which are used as the first stage to reach the speed of sound. The high speed makes it more difficult for Ukrainian defenders to disable such a missile, even for advanced systems such as the US Patriots. The difficulty of production makes the Kijals a scarce commodity; according to the Ukrainians, the Russians had about 70 of them in their arsenal and have used no more than 25 so far. Zircon is launched from submarines and frigates and, unlike the Kijal, slows down in the last stage of flight, making it an easier target for air defenses. Moscow presents the missile as a high-precision missile, which the Ukrainians say has so far failed to prove itself - it has been deployed only once, according to Kiev's documentation, in February this year in an attack on the Kiev region. Production of both types has been slow, with an estimated ten or so new missiles per month.

"In fact, the Zirkon missile is still undergoing testing for deployment in combat, as the possibilities of its use are unclear. While it is hypersonic, it is also a cruise missile and contact with satellites will only occur when it slows down to a speed of Mach 3-4. At that time it makes a lot of mistakes, so its accuracy is very questionable," aviation expert Valeriy Romanenko explained to on-line news journal Ukrainska Pravda. Thus, according to some commentators, the inconclusive results of Russia's flagship guided missile may be directly related to the wave of arrests and send a message to its own ranks.