October 16th 1962: The beginning of the Cuban missile crisis

October 16, 1962, marks the onset of the Cuban Missile Crisis, known as the Caribbean Crisis in Russia. This day set off a thirteen-day confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union that brought the world to the brink of nuclear war. The crisis unfolded after American reconnaissance discovered Soviet missile installations in Cuba, just 90 miles off the U.S. coast. It was a period of intense political and military standoff that reshaped the trajectory of the Cold War.

Background: Cold war tensions and the Cuban revolution

By 1962, the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union had reached a peak. Both superpowers were engaged in a global struggle for influence, with the U.S. committed to containing the spread of communism and the Soviet Union seeking to expand it. The Cuban Revolution of 1959, led by Fidel Castro, brought communism to America's doorstep. After overthrowing the U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista, Castro aligned Cuba with the Soviet Union, turning the island into a potential launching pad for Soviet influence in the Western Hemisphere.

In 1961, the U.S. attempted to overthrow Castro’s regime through the failed Bay of Pigs invasion. The invasion's failure left Cuba vulnerable to further American intervention and deepened Castro's ties with the Soviet Union. To protect Cuba and counter the U.S.'s nuclear advantage, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev decided to secretly deploy nuclear missiles in Cuba.

October 16, 1962: Discovery of Soviet missiles in Cuba

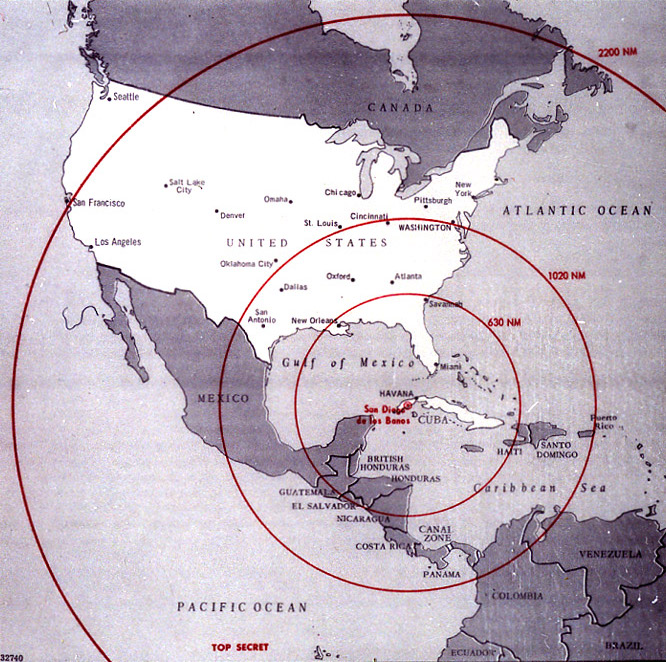

The crisis began on October 14, 1962, when a U.S. U-2 spy plane flew over Cuba and captured photographic evidence of Soviet missile installations under construction. These medium-range and intermediate-range ballistic missiles had the capability to reach major American cities, significantly altering the strategic balance. Two days later, on October 16, President John F. Kennedy was briefed on the presence of these missiles, and the Cuban Missile Crisis officially began.

Kennedy convened a group of senior advisors known as the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or "ExComm," to deliberate on a response. The discovery of the missiles presented a critical dilemma: how to remove the threat without triggering a nuclear war.

The Options: Blockade or invasion?

The U.S. faced two main options: a direct military strike on the missile sites in Cuba, which could escalate into full-scale war, or a naval blockade to prevent further delivery of Soviet missiles. After intense discussions within ExComm, Kennedy opted for a naval "quarantine" of Cuba, to prevent further Soviet shipments of military equipment to the island. The term "quarantine" was chosen over "blockade" to avoid the suggestion of an act of war.

Kennedy addressed the American public on October 22, revealing the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba and announcing the quarantine. He warned that any missile launched from Cuba would be considered a Soviet attack on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response. The announcement heightened global fears of a nuclear conflict, and citizens around the world anxiously followed the developments.

Khrushchev’s gamble and Soviet intentions

For Soviet Premier Khrushchev, the placement of nuclear missiles in Cuba was a calculated gamble. The Soviet Union was concerned about the U.S. missile deployments in Turkey and Italy, which could strike Soviet territory. By placing missiles in Cuba, Khrushchev sought to equalize the nuclear balance and secure the Soviet Union's strategic interests. Additionally, the deployment aimed to deter another U.S. invasion of Cuba and bolster the Soviet Union's position in the Cold War.

However, Khrushchev underestimated the intensity of the American response. The U.S. saw the missile deployment as an unacceptable shift in the strategic balance, a direct threat to national security that could not be tolerated.

The Thirteen Days of Crisis: Brinkmanship and negotiation

The Cuban Missile Crisis lasted from October 16 to October 28, 1962, with the world teetering on the edge of nuclear war. As U.S. naval vessels enforced the quarantine, Soviet ships approached the blockade line, raising the prospect of a direct confrontation. Meanwhile, both nations placed their military forces on high alert, with nuclear-armed bombers and missiles ready for action.

Tensions escalated on October 27, known as "Black Saturday," when a U.S. U-2 spy plane was shot down over Cuba, killing the pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson. The incident nearly triggered a U.S. military response. Simultaneously, Soviet and American leaders exchanged letters, with Khrushchev initially offering to withdraw the missiles if the U.S. promised not to invade Cuba. A second letter added a demand for the removal of American Jupiter missiles from Turkey, a condition the U.S. initially sought to keep secret.

Resolution: A secret deal and the end of the crisis

Behind the scenes, negotiations intensified. Attorney General Robert Kennedy, acting on behalf of his brother, met secretly with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. The two sides reached a compromise: the U.S. would publicly agree not to invade Cuba, while secretly pledging to remove the Jupiter missiles from Turkey within a few months. Khrushchev, facing mounting pressure at home and recognizing the danger of further escalation, accepted the deal.

On October 28, 1962, Khrushchev announced the withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Cuba, bringing the crisis to an end. In return, the U.S. lifted the quarantine and later fulfilled its promise regarding the missiles in Turkey. The resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis marked a crucial de-escalation of Cold War tensions, though it also highlighted the fragility of nuclear diplomacy.

Aftermath and impact: Lessons from the brink

The Cuban Missile Crisis had a profound impact on the Cold War dynamics and U.S.-Soviet relations. It exposed the terrifying reality of nuclear brinkmanship and the catastrophic potential of nuclear war. In the aftermath, both superpowers recognized the need for better communication to prevent such near-misses in the future. This led to the establishment of the "hotline" between Washington and Moscow, a direct communication link between the leaders of the two countries.

The crisis also marked a turning point in the nuclear arms race. It prompted a shift towards détente, or a relaxation of tensions, between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, and paved the way for future arms control agreements, such as the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963. However, the underlying ideological rivalry between capitalism and communism continued to shape global politics for decades.

For the United States, the crisis was a significant moment of leadership for President Kennedy, who was praised for his handling of the situation. However, it also left lingering tensions with Cuba, which remained a staunch Soviet ally in the Caribbean. For the Soviet Union, the withdrawal of missiles was seen as a retreat, but Khrushchev framed it as a victory for global peace.

Conclusion: October 16, 1962, and the shadow of nuclear war

October 16, 1962, was the day that set in motion one of the most dangerous confrontations in human history. The Cuban Missile Crisis not only tested the resolve of the U.S. and the Soviet Union but also highlighted the delicate balance of nuclear power during the Cold War. The decisions made during those tense thirteen days had far-reaching consequences, shaping the course of the Cold War and leaving a legacy of lessons about diplomacy, restraint, and the specter of nuclear war.

To this day, the Cuban Missile Crisis serves as a reminder of how close the world came to a nuclear conflict and the crucial importance of diplomatic engagement in resolving international disputes.